Birds inform us about the rest of the natural world, but we value them for much more than this. Over the millennia, and across all cultures, birds have given human beings inspiration, imagery and companionship; nowadays, birdwatching is a major economic force in many places. Birds are an important source of food for many communities, and the ecological services that birds provide to us are crucial and irreplaceable.

Birds embody key values in human cultures, ancient and modern View case study list

View case study list

Some of our most enduring cultural symbols are birds, reflecting the many qualities that human beings admire in them and aspire to in themselves. Cranes, parrots, hornbills, hummingbirds, kingfishers, doves, sparrows, many seabirds—all these and others have played a role in shaping the ideas and values of human societies. Birds of prey have been particularly revered, for their speed, agility and hierarchical dominance. Ancient gods such as Horus the Egyptian god of creation were often manifested as birds of prey, while eagles continue to be national symbols of strength and power to the present day. Beautiful birds, too, such as the Resplendent Quetzal in Central America (![]() ), have commanded awe and respect and feathers have provided their wearers with status and splendour down the ages (

), have commanded awe and respect and feathers have provided their wearers with status and splendour down the ages (![]() ). Today, birds are repeatedly used as logos, mascots and images that express vital qualities with which we wish to associate ourselves.

). Today, birds are repeatedly used as logos, mascots and images that express vital qualities with which we wish to associate ourselves.

Birds put life into the arts View case study list

View case study list

Given their ubiquity, activity, diurnal habits, colour and song, it is hardly surprising that birds feature so strongly in the world’s painting, poetry and music. Italian painters of the Renaissance used the Goldfinch as a religious symbol (![]() ), but throughout the western fine art tradition, from Bosch and Breughel to Picasso and Matisse, birds have played a range of roles, symbolising amongst other things the lost innocence of Eden and the great passions that nature locks inside us all. Poets have treated birds in similar fashion, from the earliest surviving manuscripts in Chinese, Persian and Latin down to the present. In music, composers down the centuries have drawn inspiration from birdsong, whether of particular birds such as Eurasian Cuckoo and European Blackbird or of the clamour and multiplicity of the dawn chorus, and culminating in the extraordinary creations of Olivier Messiaen, who believed that birds sang with the voice of God.

), but throughout the western fine art tradition, from Bosch and Breughel to Picasso and Matisse, birds have played a range of roles, symbolising amongst other things the lost innocence of Eden and the great passions that nature locks inside us all. Poets have treated birds in similar fashion, from the earliest surviving manuscripts in Chinese, Persian and Latin down to the present. In music, composers down the centuries have drawn inspiration from birdsong, whether of particular birds such as Eurasian Cuckoo and European Blackbird or of the clamour and multiplicity of the dawn chorus, and culminating in the extraordinary creations of Olivier Messiaen, who believed that birds sang with the voice of God.

Birds bring us material benefits by the million View case study list

View case study list

A detailed history of the human exploitation of birds is yet to be written, and the contribution birds have made to human development remains largely unacknowledged. However, the debt we owe them is immense. The domestication of the Red Junglefowl and the Rock Dove were seminal events for human food security in the past 10,000 years (on any one day there are some 25 billion chickens alive on earth); domesticated geese, ducks, guineafowl, turkeys and quail all make important contributions to human diets. In the past and still today wild birds and their eggs have also supplied huge amounts of food to human communities. Sometimes this exploitation has been strictly regulated (as with the megapodes (![]() )), but mostly not, losing us the Great Auk, Passenger Pigeon and many seabird colonies. Sea- and waterbird colonies supplied immense volumes of feathers for the fashion and bedding industries, the former supplemented by hummingbirds and birds-of-paradise. Seabird guano for fertiliser became so valuable to national economies that it drove major colonial expansions in the nineteenth century (

)), but mostly not, losing us the Great Auk, Passenger Pigeon and many seabird colonies. Sea- and waterbird colonies supplied immense volumes of feathers for the fashion and bedding industries, the former supplemented by hummingbirds and birds-of-paradise. Seabird guano for fertiliser became so valuable to national economies that it drove major colonial expansions in the nineteenth century (![]() ). A review of modern-day usage reveals the huge extent to which we continue to use wild birds for our own ends today (

). A review of modern-day usage reveals the huge extent to which we continue to use wild birds for our own ends today (![]() ).

).

Birds supply vital ecological and social services View case study list

View case study list

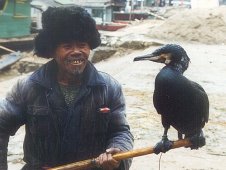

Among the vertebrates it is birds that provide the greatest restraint on insect populations (![]() ), though the role of bats is also crucial. Many birds such as pigeons, hornbills and birds-of-paradise are important as dispersers of seeds, particularly in tropical forests, and some, including lorikeets, hummingbirds and sunbirds, are key pollinators of plants. In human societies birds are or have been put to a remarkable range of uses, including the disposal of corpses (vultures), the gathering of food (trained cormorants) and delivery of messages (pigeons). In the domestic environment it is as singing and speaking companions (many species, especially parrots and finches) that their presence is most widely felt. In the wild, the twin occupations of birdwatching and sport hunting (particularly wildfowling and falconry) are pursued by millions worldwide, generating a major source of income in many areas. Their habitats provide further ecosystem services (

), though the role of bats is also crucial. Many birds such as pigeons, hornbills and birds-of-paradise are important as dispersers of seeds, particularly in tropical forests, and some, including lorikeets, hummingbirds and sunbirds, are key pollinators of plants. In human societies birds are or have been put to a remarkable range of uses, including the disposal of corpses (vultures), the gathering of food (trained cormorants) and delivery of messages (pigeons). In the domestic environment it is as singing and speaking companions (many species, especially parrots and finches) that their presence is most widely felt. In the wild, the twin occupations of birdwatching and sport hunting (particularly wildfowling and falconry) are pursued by millions worldwide, generating a major source of income in many areas. Their habitats provide further ecosystem services (![]() ), including carbon storage.

), including carbon storage.

Birds are major drivers of science and human self-knowledge View case study list

View case study list

Birds have played a key role in many important developments in the life sciences. Darwin’s groundbreaking idea, evolution through natural selection, was inspired by Galápagos finches and shaped by the contemplation of pigeon varieties. The biological species concept was developed by an ornithologist, ethology (the study of animal behaviour) was advanced through the study of geese, gulls and crows, and behavioural ecology has many of its roots in work on the Dunnock and Arabian Babbler (![]() ). More immediately, the use of birds as environmental monitors has many significant applications bearing on human welfare. These range from documenting the reality of climate change and tracking the deteriorating status of planetary biodiversity, to determining the presence and influence of pollutants in particular aquatic and agricultural ecosystems.

). More immediately, the use of birds as environmental monitors has many significant applications bearing on human welfare. These range from documenting the reality of climate change and tracking the deteriorating status of planetary biodiversity, to determining the presence and influence of pollutants in particular aquatic and agricultural ecosystems.