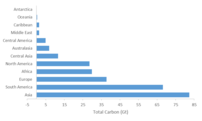

IBAs provide a wide range of services that benefit humans locally, regionally and globally. For example the provision of wild food and the purification of water, as well as opportunities for cultural, spiritual and recreational experiences. The global network of IBAs stores an estimated 300 gigatonnes of carbon in above and below ground vegetation and soil organic carbon, representing almost 9% of the world’s total terrestrial carbon stock. They therefore make a significant contribution to regulating our climate.

Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) are sites of global significance, based on the presence of species of world-wide conservation concern. These areas of natural or semi-natural habitat also provide a wide range of ecosystem services to people. These include the provision of wild food, medicinal plants, fibres, the purification and regulation of water, global climate regulation as well as opportunities for cultural, spiritual and recreational experiences and much more. In many cases, IBAs directly support the livelihoods of local people living in and around them (BirdLife International 2007) through the ecosystem services that they provide. For example, at Koshi Tappu Wildlife Reserve in Nepal, the communities living in the buffer zone benefit from permitted access for fishing and harvesting of products such as Typha for mat-weaving and grasses for thatch and livestock fodder.

Ecosystem services from sites such as IBAs or protected areas often provide benefits to a range of stakeholders at different spatial scales (Fisher et al. 2009). Hence it is not only local communities that benefit from the services provided by IBAs. Many IBAs provide watershed services to downstream users, often large cities, such as the Western Area Peninsula Forest Reserve in Sierra Leone which provides much of the water for the one million people living in the country’s capital city, Freetown. The network of IBAs is also important for global climate regulation. Terrestrial IBAs contain around 300 gigatonnes of carbon in above- and below-ground biomass and soil organic carbon – almost 9% of the world’s total terrestrial carbon stocks. (Analysis of data in Bouvet et al. 2018, ESA 2017, Hengl 2017, Santoro 2018, Spawn et al. 2017, Xia et al. 2014).

Another benefit that we receive from nature are recreational opportunities. Nature-based tourism is frequently described as one of the fastest growing sectors of the world's largest industry, and a very important justification for conservation (Balmford et al. 2009). In England, surveys show that over half of the adult population visits the natural environment at least once a week. In total, the English adult population participated in an estimated 2.73 billion visits to the natural environment during 2011/12, spending approximately £20 billion (Natural England 2012). This activity is particularly important in providing financial resources for protected areas, such as the National Parks in Africa, many of which are also IBAs.

In some cases, it is possible to estimate the economic value of certain ecosystem services to society through applying both market and non-market monetary values. For example, Costanza et al. 1997 estimated the world’s ecosystem services to be worth $33 trillion every year. More recently, an international study raised the profile of biodiversity conservation efforts by estimating the economic impact of losing biodiversity at the global scale. TEEB (2010) presented strong evidence to show that conserving biodiversity makes economic sense. Studies such as these have raised increasing awareness within the policy arena about the importance of considering ecosystem services arguments in support of biodiversity conservation.

BirdLife, working in collaboration with five other institutions, has developed a novel toolkit for assessing ecosystem services at sites of conservation importance (Peh et al. 2013). This was developed and piloted across a range of sites and habitats globally and it is now being used by practitioners across the globe. The results from the application of this toolkit across IBAs are being used by BirdLife Partners to inform site management and to support advocacy, enhancing biodiversity conservation. For more information on the toolkit (TESSA: Toolkit for Ecosystem Service Site-based Assessments, see here).

Related Case Studies in other sections

Links

References

Balmford, A.P., Beresford, J., Green, J., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M. and Manica, A. (2009) A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PLOS Biology 7(6): 1–6.

BirdLife International (2007) The BirdLife International Partnership: Conserving biodiversity, improving livelihoods. Cambridge, UK; BirdLife International.

Bouvet, A., Mermoz, S., Le Toan, T., Villard, L., Mathieu, R., Naidoo, L., and Asner, G. P. (2018). An above-ground biomass map of African savannahs and woodlands at 25 m resolution derived from ALOS PALSAR. Remote Sens. Environ. 206: 156–173.

Costanza, R., Darge, R., Degroot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K., Naeem, S., Oneill, R. V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R. G., Sutton, P., and Vandenbelt, M. (1997) The value of the world's ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387 (6630): 253–260.

ESA (2017) Land Cover CCI Product User Guide Version 2. Tech. Rep. Available at: maps.elie.ucl.ac.be/CCI/viewer/download/ESACCI-LC-Ph2-PUGv2_2.0.pdf

Fisher, B., Turner, R. K. and Morling, P. (2009) Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision-making. Ecological Economics 68: 643–653.

Hengl T., Mendes de Jesus, J., Heuvelink, G. B. M., Ruiperez Gonzalez, M., Kilibarda, M., Blagotić, A., Shangguan, W., Wright, M. N., Geng, X., Bauer-Marschallinger, B., Guevara, M. A., Vargas, R., MacMillan, R. A., Batjes, N. H., Leenaars, J. G. B., Ribeiro, E., Wheeler, I., Mantel, S. and Kempen, B. (2017) SoilGrids250m: Global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12(2): e0169748.

Natural England (2012) Monitor of engagement with the natural environment: The national survey on people and the natural environment. Natural England Commissioned Report NECR094. Peterborough, UK; Natural England. [Available at: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/1712385?category=47018]

Peh, K. S.-H., Balmford, A. P., Bradbury, R. B., Brown, C., Butchart, S. H. M., Hughes, F. M. R., Stattersfield, A. J., Thomas, D. H. L., Walpole, M., Bayliss, J., Gowing, D., Jones, J. P. G., Lewis, S. L., Mulligan, M., Pandeya, B., Stratford, C., Thompson, J. R., Turner, K. and Birch, J. C. (2013) TESSA: A toolkit for rapid assessment of ecosystem services at sites of biodiversity conservation importance. Ecosystem Services. 5: 51-57.

Santoro, M. (2018) GlobBiomass - global datasets of forest biomass. PANGAEA.

Spawn, S. A., Lark, T. J. and Gibbs, H. K. (2017) A New Global Biomass Map for the Year 2010. Orleans, LA: American Geophysical Union.

TEEB (2010) The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: ecological and economic foundations. Earthscan.

Xia, J., Liu, S., Liang, S., Chen, Y., Xu, W. and Yuan, W. (2014) Spatio-temporal patterns and climate variables controlling of biomass carbon stock of global grassland ecosystems from 1982 to 2006. Remote Sensing 6: 1783-1802.

Compiled: 2013 Last updated: 2020

Recommended Citation:

BirdLife International (2020)

IBAs deliver valuable ecosystem services to local people and the wider community.

Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/ibas-deliver-valuable-ecosystem-services-to-local-people-and-the-wider-community on 23/12/2024