There is a time lag before habitat destruction causes the extinction of a species. A study in Kenya suggested that the number of species in habitat fragments declines exponentially after isolation, with half the number of species that are expected eventually to disappear being lost in the first 23-80 years following isolation. Another study in insular South-East Asia revealed that the totals of threatened bird species in the region’s island archipelagos showed close correlation with the number of extinctions predicted by forest loss data.

The wholesale destruction of tropical habitats, most notably forests, is predicted to cause mass extinctions of species from all taxon groups. In practice, however, relatively few confirmed extinctions have been documented in the continental tropics, leading some critics to dismiss the postulated ‘extinction crisis’ as exaggerated and alarmist. There is, however, no room for complacency. Numerous procedural and political complications can delay the final declaration of a species as extinct. More importantly, there is a time-lag before the last individuals of a species disappear.

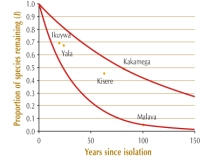

The number of extinctions expected as a result of habitat loss can be estimated using the well-established relationship between the number of species found in an area and its size. Few studies have attempted to quantify the time-scales over which such extinctions occur. However, one investigation in Kakamega Forest, Kenya, suggested that the number of species in habitat fragments declines exponentially after isolation, with a half-life of 23–80 years. In other words, half the number of species that are expected eventually to disappear are lost in the first 23–80 years following isolation (Brooks et al. 1999; see figure a). The variation is caused by differences in fragment size and degree of isolation.

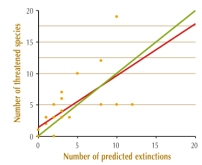

Further support for the existence of a time-lag is provided by analyses that compare numbers of threatened species with levels of habitat loss in a region. One such study in insular South-East Asia revealed that the totals of threatened bird species in the region’s island archipelagos showed close correlation with the number of extinctions predicted by forest loss data (Brooks et al. 1997; see figure b). As threatened species are those at high risk of extinction, this correlation lends support to the idea that recent deforestation and habitat fragmentation is having a much greater impact than implied by documented recent extinction rates. The intimate relationship between habitat loss and extinction is further emphasised by data from areas that have been deforested for relatively long periods of time. In Singapore, for example, where forest cover is now less than 5% of its original area, 61 of the territory’s 91 forest-dependent bird species have disappeared since 1923 (Castelletta et al. 2000).

These studies help to explain the discrepancy between the numbers of predicted and observed extinctions and highlight the critical time-scales over which conservation actions are required. Without immediate action, many species threatened by habitat loss will indeed become extinct.

References

Compiled: 2004

Recommended Citation:

BirdLife International (2004)

Time lags mean that current extinction rates are underestimated.

Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/time-lags-mean-that-current-extinction-rates-are-underestimated on 23/12/2024