BirdLife’s Important Bird Area (IBA) monitoring framework uses a two-tier system to obtain both breadth (coverage of the entire IBA network) and depth (more intensive effort at a sample of sites). This approach has been piloted by BirdLife Partners in Africa, and is under development in Europe and elsewhere.

Monitoring is costly. Especially in developing countries, many monitoring systems have failed because they are over-ambitious. Systems that rely on expensive equipment and highly trained personnel are often difficult to sustain. Yet data must be collected systematically and to a high standard, or they will be worthless. Monitoring will become increasingly important under climate change; it will enable us to understand how species are responding, and how effective implemented conservation actions are.

BirdLife’s Important Bird Area (IBA) monitoring framework for Africa (Bennun 2003) uses a two-tier system to obtain both breadth (coverage of the entire IBA network) and depth (more intensive effort at a sample of sites). Basic IBA monitoring involves regular assessment, usually once per year, of every IBA against indicators of state, pressure and response. The data required are simple and mainly qualitative. They can be collected on site by management authority staff, Site Support Groups (SSGs), project workers,members of the BirdLife Partner or other volunteers. Qualitative data are scored to give an overall rating for each site.

Detailed IBA monitoring takes place at a sub-set of priority sites, where capacity permits. The monitoring design varies but is tightly linked to site conservation objectives. It is always designed to be as simple, robust and inexpensive as possible. Existing bird counting schemes, such as the African Waterbird Census co-ordinated by Wetlands International (Dodman et al. 1998), are linked closely into the IBA monitoring programme.

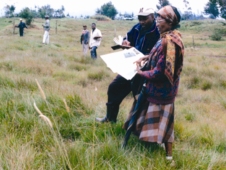

As well as keeping the monitoring methods cost-effective, it is important to institutionalise the work. This means that organisations based at the site, such as a parks authority or SSG, carry out monitoring as part of their routine activities. For example, members of three branches of the Friends of Kinangop Plateau, an SSG in Kenya, are monitoring three separate areas of the Kinangop Grasslands IBA. In a carefully selected set of sample fields the monitoring teams count numbers of Sharpe’s Longclaw Macronyx sharpei (Endangered), assess grassland condition and measure areas converted from grassland to cropland (or vice versa).

Once given some initial training, the individuals involved should be able to continue monitoring with only occasional help and supervision. This necessitates a fully participatory approach, so that the monitors ‘own’ both the process and the data. Those on the ground also need to receive relevant feedback on the information they provide, so continuing investment is needed in national co-ordination.

The IBA monitoring framework is now being implemented by the BirdLife Partnership in around a dozen countries across Africa, and a similar framework is under development in Europe and elsewhere.

This case study is included in ‘The Messengers: What birds tell us about threats from climate change and solutions for nature and people’. To download the report in full click here.

Related Case Studies in other sections

Related Sites

Related Species

References

Compiled: 2004 Last updated: 2015 Copyright: 2015

Recommended Citation:

BirdLife International (2015)

BirdLife Partners have developed a monitoring framework for IBAs worldwide.

Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/birdlife-partners-have-developed-a-monitoring-framework-for-ibas-worldwide on 22/12/2024