Reform of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has reduced negative impacts on farmland birds. Where appropriate targeted agri-environmental schemes have been deployed, populations of some rare and localised bird species have recovered.

For several decades, the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has been a main driver of the decline of farmland birds in Europe. Guaranteed prices and production subsidies have led to massive intensification of farming, often well beyond what would have happened under market pressure alone. Recent reforms have removed artificial incentives to intensification by breaking the link between subsidies and production. Some basic conditions relating to minimal good practice must now be met before subsidies can be received. New funding streams, targeting rural development and environmental concerns have also been introduced.

Advocacy by BirdLife International and its national Partners has been instrumental in bringing about these changes. While these reforms have lessened the negative impact of the CAP and allowed for some conservation to take place, the current policy still broadly fails the environment. A key problem is that most funding still goes to the most intensive farming systems, rather than supporting sustainable farming.

Agri-environment schemes (AES) are contracts by which farmers are paid to improve their land management practices to benefit biodiversity and the wider environment. Despite some well-publicised examples of poorly-targeted and under-monitored AES failing to deliver for biodiversity (e.g. Kleijn et al. 2001, Kleijn and Sutherland 2003), there is also a growing body of evidence showing that well-targeted, science-based AES schemes can deliver spectacular results in reversing the decline of farmland birds and other biodiversity (e.g. Wotton and Peach 2007, Knop et al. 2006, Brereton et al. 2005).

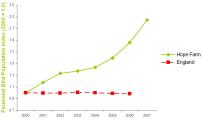

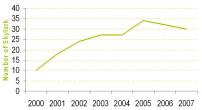

For example, at Hope Farm (an arable farm in Cambridgeshire, UK, owned by the RSPB / BirdLife in the UK and managed to demonstrate that wildlife-friendly measures can be integrated with profitable commercial cropping), monitoring has shown a rapid increase in the local population of numerous farmland bird species, most of which have declined or are still declining at national level. One of these species, Skylark Alauda arvensis, has increased three-fold at Hope Farm following the implementation of a targeted option providing micro-habitats within cultivated fields (see figures a and b).

The Skylark declined rapidly in the UK from the mid 1970s until the mid 1980s, probably because of the change from spring to autumn sowing of cereals. This practice restricts opportunities for late-season nesting attempts, because the crop is by then too tall, and may depress overwinter survival by reducing the area of stubbles (Wilson et al. 1997, Donald and Vickery 2000). Leaving small, rectangular patches of bare ground ('Skylark plots') within autumn-sown cereals appears to provide many of the benefits of spring-sown cereals at very low cost to the farmer (Donald and Morris 2005).

However, with AES currently accounting for only around 8% of the overall CAP budget (Farmer et al. 2009), and voluntary payments struggling to compete with high commodity prices, saving Europe’s farmland birds still requires a fundamental overhaul of EU policy if successes achieved at local scales are to be scaled up to national and continental levels.

Related Species

References

Compiled: 2008

Recommended Citation:

BirdLife International (2008)

BirdLife Partners are supporting reform of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/birdlife-partners-are-supporting-reform-of-the-eu’s-common-agricultural-policy on 22/12/2024