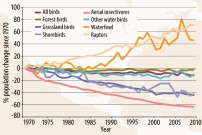

The State of Canada’s Birds report (www.stateofcanadasbirds.org) shows the strong influence of human activity on bird populations over the last 40 years, and highlights the urgent need for bird conservation action. Aerial insectivores, grassland birds, and Arctic shorebirds have declined dramatically since 1970. Waterfowl and raptor populations are rebounding thanks to conservation efforts.

In 2012, the North American Bird Conservation Initiative Canada steering committee—which includes Canadian BirdLife co-partners Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada—released the first comprehensive report on the health of Canada’s birds. The State of Canada’s Birds report drew on 40 years of data from professionals and citizen scientists to present an overview of how Canada’s birds are faring. The results show the strong influence of human activity on bird populations since 1970, and highlight the urgent need for bird conservation action.

The report finds that there are fewer birds now than in 1970, the year effective monitoring began for most species. On average, Canadian breeding bird populations have declined by 12%. More species are decreasing (44% of species in Canada) than increasing (33%), while 23% have shown little overall change. Some groups have severely declined, including grassland birds, migratory shorebirds, and aerial insectivores. These groups have all decreased by more than 40%, on average, and some individual species in these groups have decreased by more than 90%.

Aerial insectivores—swallows, flycatchers, and other birds that catch insects in flight—are declining more steeply than any other group of birds; possible causes include reductions in insect numbers, habitat loss, pesticide use, and climate change. Grassland birds (including longspurs, meadowlarks, Sprague’s Pipit, Greater Sage-Grouse, and others) have also declined dramatically, due largely to a loss of habitat. Shorebirds have declined by almost half overall; Arctic shorebirds in particular, including the endangeredregionally threatened Red Knot, have declined by 60%.

Other species are recovering as a result of successful conservation efforts. Increasing raptor populations (for species such as the Peregrine Falcon, Osprey, and Bald Eagle) point to the success of direct conservation actions, including pesticide controls. Waterfowl populations (ducks and geese) are also rebounding, in part due to effective management of wetlands and hunting.

International collaboration is essential to achieve conservation success. Only 22% of Canadian bird species spend the entire year in the country. Most others migrate to the United States (33%), to Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean (23%), or to South America (15%). The biggest threats for many species during their long migrations are habitat loss at stopover sites and on their wintering grounds. However pollution, pesticides, hunting, collisions with human-built structures, and climate change also have effects. Investment in the monitoring and conservation of birds and their habitats supports a healthy environment for people.

References

Compiled: 2013

Recommended Citation:

BirdLife International (2013)

More bird species groups in Canada are in decline, than are increasing.

Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/more-bird-species-groups-in-canada-are-in-decline-than-are-increasing on 23/12/2024