Community forestry in Nepal forms an important part of a national strategy for livelihoods improvement and environmental protection. A recent study conducted by Bird Conservation Nepal (BCN, BirdLife in Nepal) assessed the status and trends of biodiversity at the site and the provision of ecosystem services benefits to people locally. The study found that community forestry has improved biodiversity conservation and management and sustainability of resource use to local communities although some of the benefits from the IBA are not being captured at the local scale or by the most marginalised groups. Hence, targeted development, such as ensuring that local communities benefit from the revenues generated by visiting tourists, can help towards improving livelihoods of these communities.

Many of Nepal’s forests are managed by community Forest User Groups (FUGs) in accordance with plans approved by the District Forest Office. There are over 14,500 FUGs in Nepal (Ojha et al. 2009), and most are coordinated and represented by an umbrella organisation, FECOFUN (Federation of Community Forestry Users Nepal). Many of the unprotected Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas (IBAs) in Nepal are managed in this way, and the FUGs are therefore natural local partners to work with Bird Conservation Nepal (BCN, BirdLife in Nepal) for conservation and development at these sites.

Phulchoki Mountain IBA is located 16 km southeast of Kathmandu. The lower slopes of the mountain support a luxuriant growth of subtropical broadleaved forest and the site is particularly important for the restricted-range bird species Spiny Babbler Turdoides nipalensis, Hoary-throated Barwing Actinodura nipalensis and significant populations of species characteristic of the Sino-Himalayan Temperate Forest biome (Baral and Inskipp 2005, BirdLife International 2011). IBA monitoring data collected by BCN on the key bird species and their forest habitats, and held in BirdLife International’s World Bird Database, suggest that pressures on biodiversity at the Phulchoki Mountain Forest IBA have reduced and that its state has improved over recent years (2004–2011), i.e. under community forestry.

Because of its proximity to Kathmandu many people are attracted there at weekends, to picnic in ‘parklands’ on the forest’s boundary or to enjoy the snow during winter. It is also an accessible site for bird-watchers with significant potential for international tourism. In 2004, BCN recognised that communities were receiving little benefit from the thousands of national visitors coming to the forest each year. Since that time much of BCN’s support to the FUGs has been focused on enhancing the revenue that they can earn from these visitors. BCN helped five FUGs to improve facilities and put in place a more organised charging system. Each FUG identified their own priorities, which included improving the water supply, constructing toilets, building tables, chairs and shelters, fencing and erecting signboards. Their efforts have made a significant difference to the income that they receive. At Godavari Kunda, for example, the community was receiving about Rs 5000 (US$70) from picnickers. However, since the improvements to the picnic area, they have auctioned the annual lease to run the picnic site to members of the FUG and now receive about 65,000 Rs (US$900) a year (Thomas 2011). These funds contribute to forest patrolling and FUG management costs, but they are also used for projects in the village—including improvements to the roads and bursaries for school children from some of the poorest households.

This study showed that, compared to an alternative state whereby community forestry had not been established at Phulchoki forest and no picnic sites had been developed, the net benefits coming directly to these FUGs would amount to $8 600 / year. The wider value of the site for nature-based recreation was calculated as $750 000 / year from the visitor spend on local transport, food and other goods (Birch et al. submitted). However, the financial benefit from this is often not captured locally, but contributes to national tour operators or the general economy.

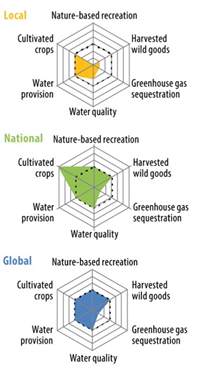

In addition to increased benefits from nature-based recreation, management for community forestry results in better provision of ecosystem services such as harvested wild goods (fuelwood, fodder, compost), global climate regulation and water quality (Birch et al. submitted). Whilst local people are capturing (and controlling) most of the benefits from harvested wild goods, recreational visitors and improved water quality compared to the alternative state, there are other benefits which accrue to more distant users, such as the global benefit of climate regulation from carbon storage and greenhouse gas sequestration and much of the wider nature-based recreation value. To provide more financial benefits at the local level, further improvements to the infrastructure around the forest, could increase the attraction of the site to visitors, especially international tourists, and bring more revenues to the FUGs. Training of local guides in bird identification to work with the national tour operators would increase the proportion of benefits going direct to the communities and would reward them for their sustainable management of forest resources. However, there are also issues surrounding the distribution of benefits at the local level, with reports of poor and lower castes still being marginalized. Any development of livelihood activities at the site should therefore consider carefully the equitable distribution of these benefits.

Related Case Studies in other sections

Related Sites

Related Species

Links

References

Compiled: 2011 Last updated: 2013 Copyright: 2013

Recommended Citation:

BirdLife International (2013)

Local communities around Phulchoki Important Bird Area in Nepal benefit from tourism.

Downloaded from https://datazone.birdlife.org/local-communities-around-phulchoki-important-bird-area-in-nepal-benefit-from-tourism on 22/12/2024